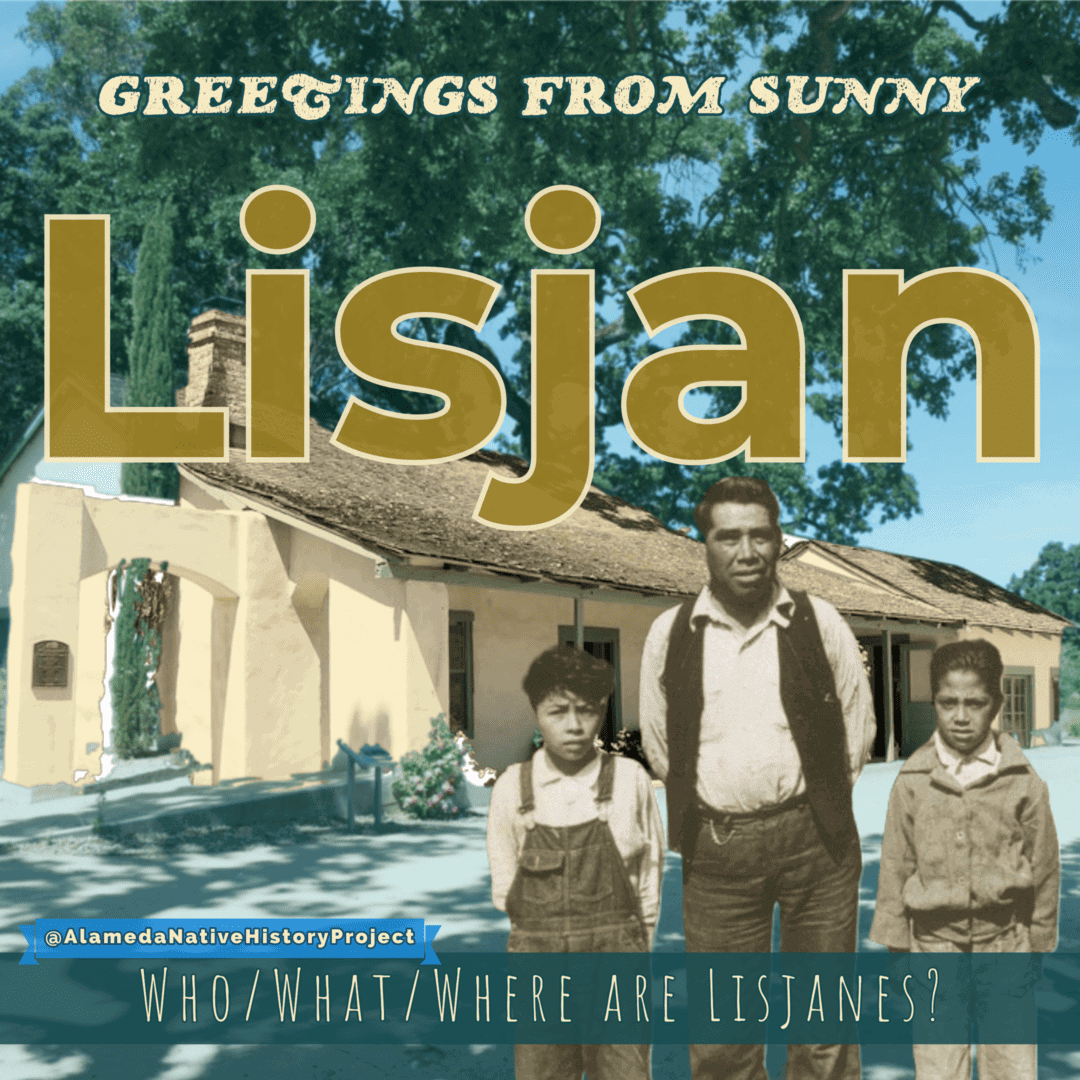

“Lisjan” has been referred to as a Traditional Ohlone Village Site, in East Oakland.

Both the San Leandro Creek, and San Lorenzo Creek bear the name of “Lisjan” creek.

But “Lisjan” isn’t even an Ohlone word.

“Lisjan” is what Nisenan People call the city of Pleasanton, California.

And, just to be clear: Pleasanton wasn’t called “Pleasanton” until the 1860’s. Up to that point, it was called “Alisal”, or “Alizal”, or “El Alizal”, or “Alisal Rancheria”. And, before that, Alisal was the Bernal Rancheria.

And Nisenan People are not Maidu People. They’re totally seperate tribes.

You could say, the present day Nisenan capitol is Nevada City, California….

The “definition” of Lisjan, a Nisenan Word…

In 1929, A.L. Kroeber published “The Valley Nisenan“, which contained an expansive, and categorized Nisenan vocabulary; and a decent explanation of phonetics. However, this was only a short list, which did not contain Place Names. But, this book is an indication of the linguistic study and research going on behind the scenes, in California, in the early 20th century.

It wouldn’t be until 1966, that Hans Jørgen Uldall, would publish “Nisenan Texts and Dictionary“, with William Shipley. This volume includes some very adult stories. So, beware. But, there are Nisenan-English, and English-Nisenan dictionaries in the back.

Uldall’s dictionary contains the entry for “Lisjan”; as a Place Name for Pleasanton, California.

But, how did that name, get all the way up to Nisenan territory, 100 miles away from Pleasanton? And 45 years after Harrington’s interviews? Why is “Lisjan” being touted as a traditional Ohlone Village Site in deep East-Oakland, if “Lisjan” is another name for Pleasanton?

J.P. Harrington’s “Chochenyo Field Notes” (1921)

One of the most-cited references in Ohlone History…

In 1921, J.P. Harrington performed a Language Survey of Native Americans in the East Bay. Harrington gathered numerous languages during this time, including the “Chocheño” language; which is known as the East Bay Ohlone language, today. Despite being deeply flawed, and extremely sus at times, this document continues to be a primary influence on mainstream discussions about Ohlone History in the San Francisco Bay Area.

One of Harrington’s interviewees was a man by the name of Jose Guzman. Guzman was interviewed, along with a man named “Angelo”, and a third man who is known as “informant”–presumably, Harrington’s fixer. Francisca is another interviewee who appears separately from Jose and Angelo, most times.

As a digital file this document is 2.3 gigabytes large. It has 355 pages of original scans. It is entirely hand-written in cursive. [J. Alden Mason’s “Plains Miwok, Chocehnyo Field Notes”, from 1916, actually are written in cursive.] And uses a mix of Chochenyo, Spanish, and English (in that order.)

This volume is incredibly informative. Even though, a good portion of the information provided by Jose Guzman, and Angelo become problematic in many places–when viewed in context with later anthropological work, and the lack of clear attribution to a speaker (if any) in many of the entries. This is a problem with Harrington, really.

A majority of contemporary work on East Bay Ohlone People cite J.P. Harrington’s “Chochenyo Field Notes”, from 1921.

This document is never more than one step removed from almost any article or research paper.

But who’s actually read it? As daunting as these tomes look in the beginning: I have to be honest, and tell you, it’s not as bad as it seems. 355 pages of hand-written notes goes kind of quickly if you can hang with the kind of Spanglish that’s spoken on many a rez, today.

It’s easy to get a feel for the personalities of the interviewees by how their interviews progress; and even the type of setting. Some interviews were taken at gatherings. There are write-ups of methods of fabrication for food and tools; songs; as well as old stories, passed down to Jose Guzman. Harrington’s hand-writing also changes, depending on the speed of the information he’s being given, and whether or not he’s having a good day. Sometimes, he had to switch pens, until ultimately finding a pencil.

In the beginning, Harrington focuses on the basics. Where are you from? What’s the name of your tribe? Have you heard of these people? Can you tell me the history of this place?

Harrington wouldn’t ask twice about something the same day. He would circle back to it again, on another day.

As his notes progress, the words move to phrases. The lists become Chocheño lists, with Spanish or English translation.

This is how “Lisjan” kept popping up.

Harrington’s Synthesis of Chocheño VS. The Way Chocheño Was Actually Being Spoken

Aside from where the notes explicitly said who the speaker was, or whether or not the interviewees agree, it’s difficult to tell the difference between Harrington’s own ideas and synthesis of Chocheño; and the Chocheño language as it was actually spoken.

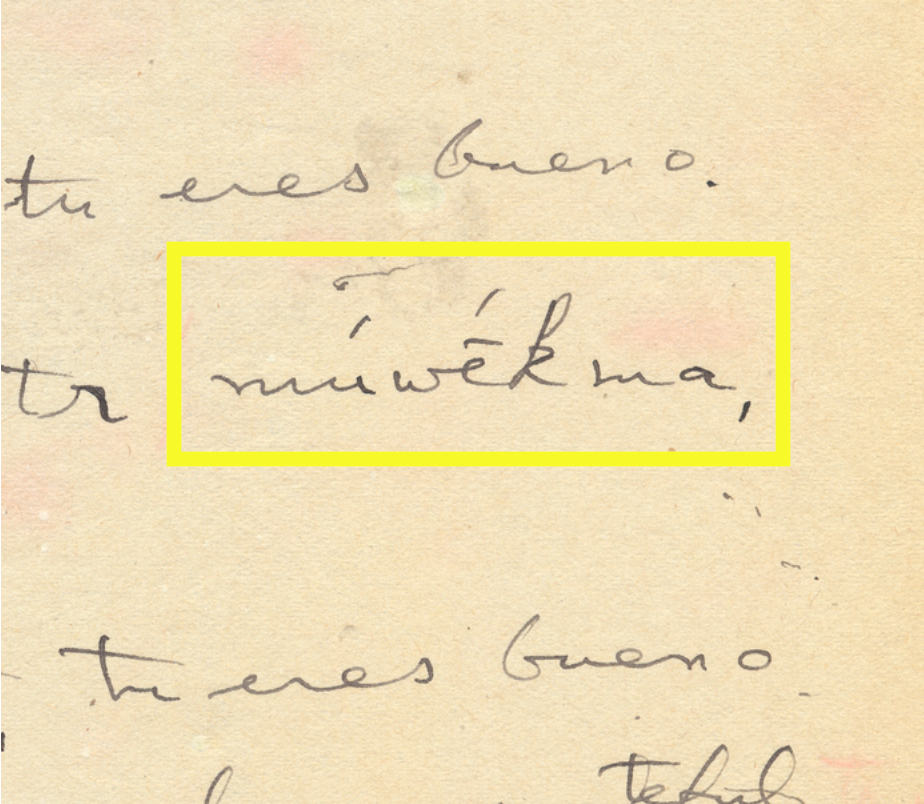

The following entry shows how Harrington took a variation of the phrase “makin miwikma” (we are good people), and applied it to “lisjan”, to form “lisjanikma”–which, to Harrington’s understanding of Chocheño, means “lisjan people”.

makin lisjanikma, we are lisjanes. approved lisjanikma but could not get tongue around it.”

The result was a valid form of the word. But not a word which was actually in use; or even really pronounceable.

This would continue on the next page, with:

makin Jinijmin, somos muchachos, cannot say *makin jinijminka inf. tells me clearly

‘aji jinijmin mak[n]ote, puros muchachos estamos aqui”

Hand-writing is unclear for “mak[n]ote”, “mak[in]ote”, “mak[s]ote”, “mak[‘n]ote”…

This is when I started suspecting there may have been drinking involved in some of these later sessions with Jose Guzman and Angelo. (Because it looks like they’re having fun, and getting kinda goofy at times.) The informant’s answer seems to say more about the philosophy, or [machismo] culture, of the group being interviewed. I can actually see it playing out:

You can’t just say, “We’re some men.”

You have to say, “Puros muchachos estamos aqui!”

It was at this point, that I started noticing the strong Spanish-language influence in many of these examples of Chocheño given to Harrington by Chocheño speakers.

References to “Lisjan”

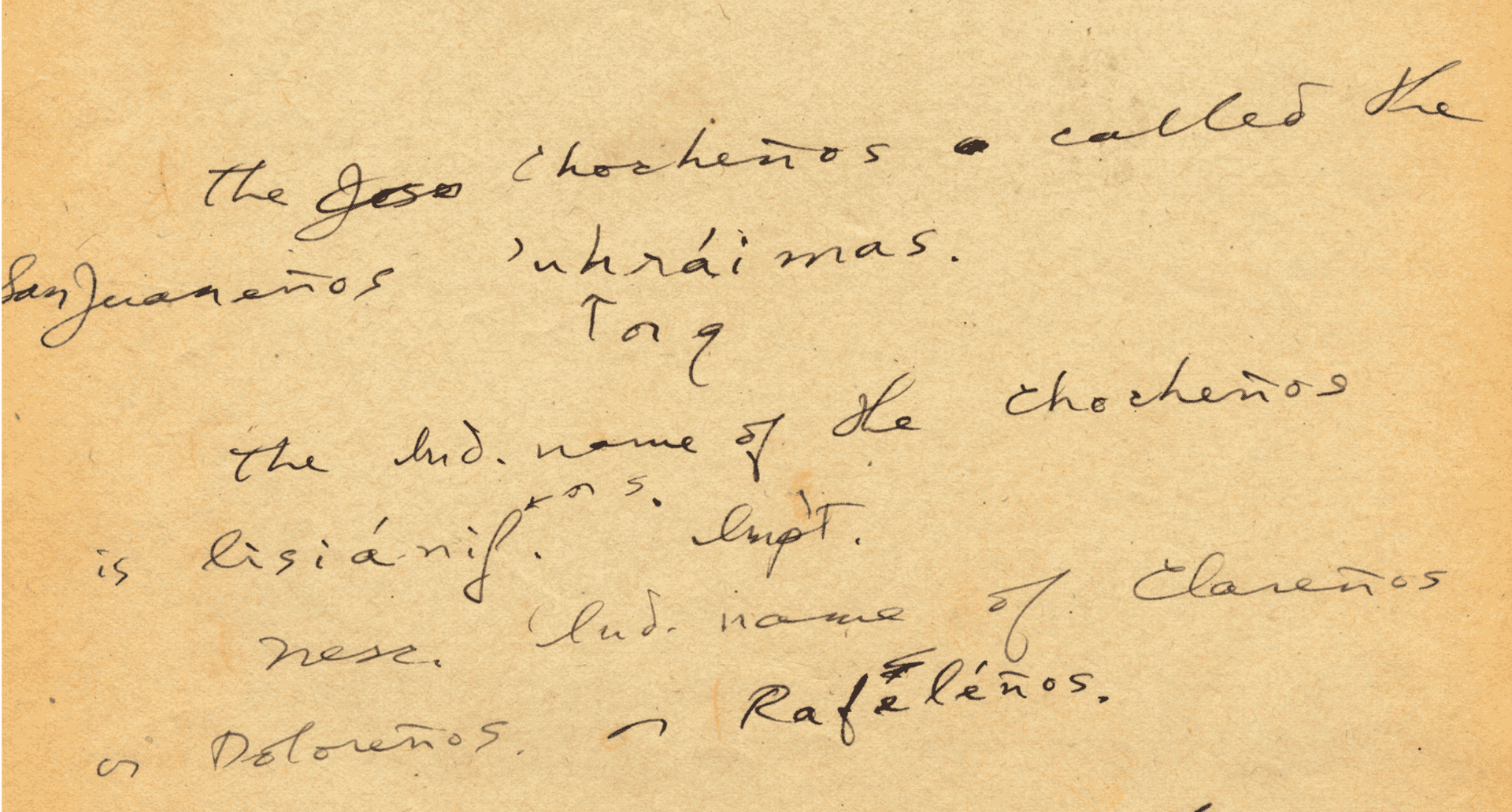

The Ind. name of the Chocheños is lisianij.

In the first few pages, we find an entry that says the “Indian Name” of the Chocheños is “Lisjan“.

This may seem like an authoritative, and all-encompassing reference. But the specifics change over time.

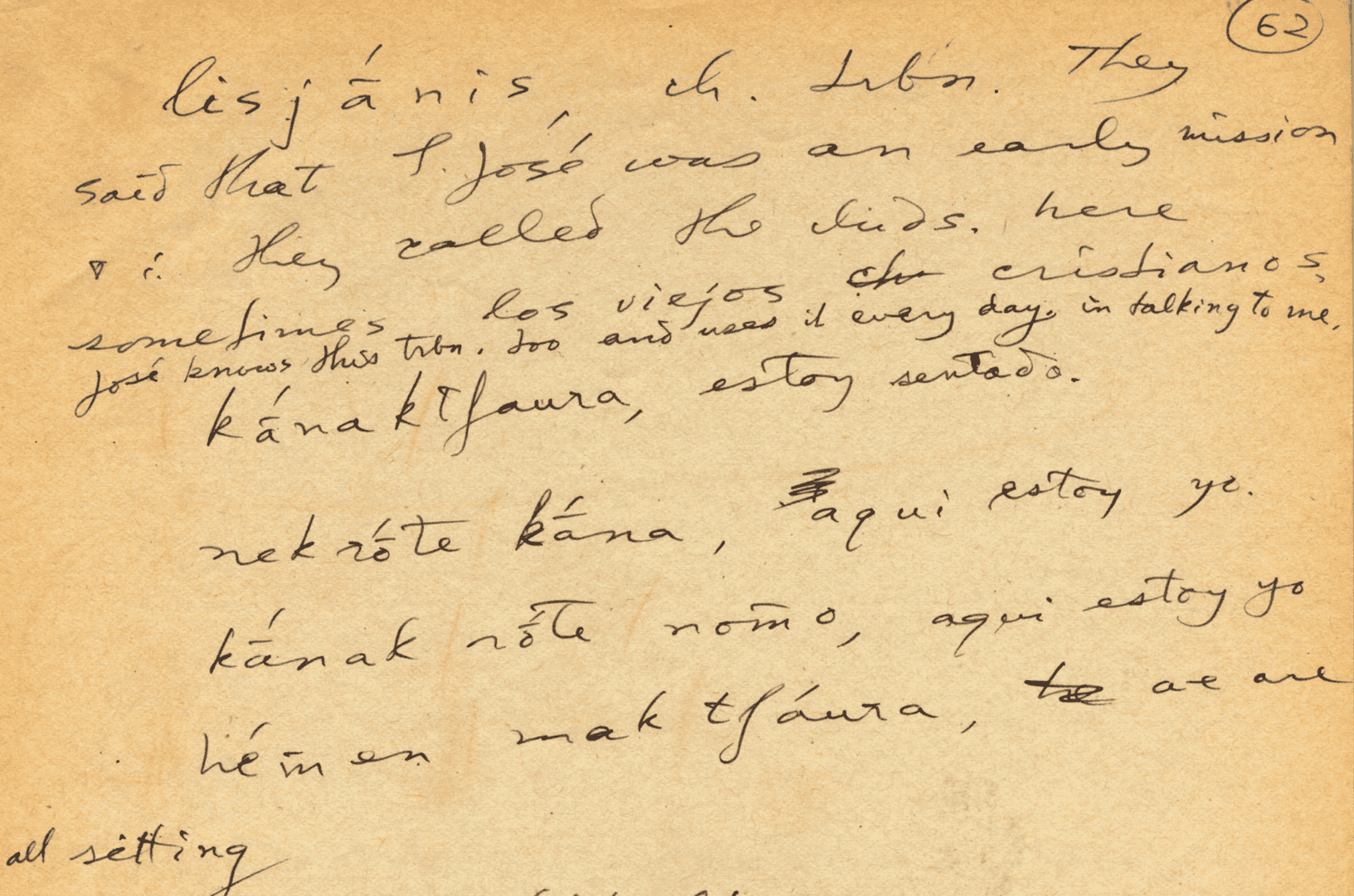

lisjanis, In. Infor. They said that S.Jose was an early mission [upside-down triangle symbol]; they called the Inds. here sometimes los viejos cristianos. Jose knows this trbu. too and uses it every day, in talking to me.

In the next entry, we find out that San Jose Mission Indians were also called “los viejos cristianos”.

We also find out that Jose Guzman references San Jose Mission Indians this way, as well. No location information is given yet. But that changes.

Soon, there are distinctions made between who is, and who isn’t Lisjan.

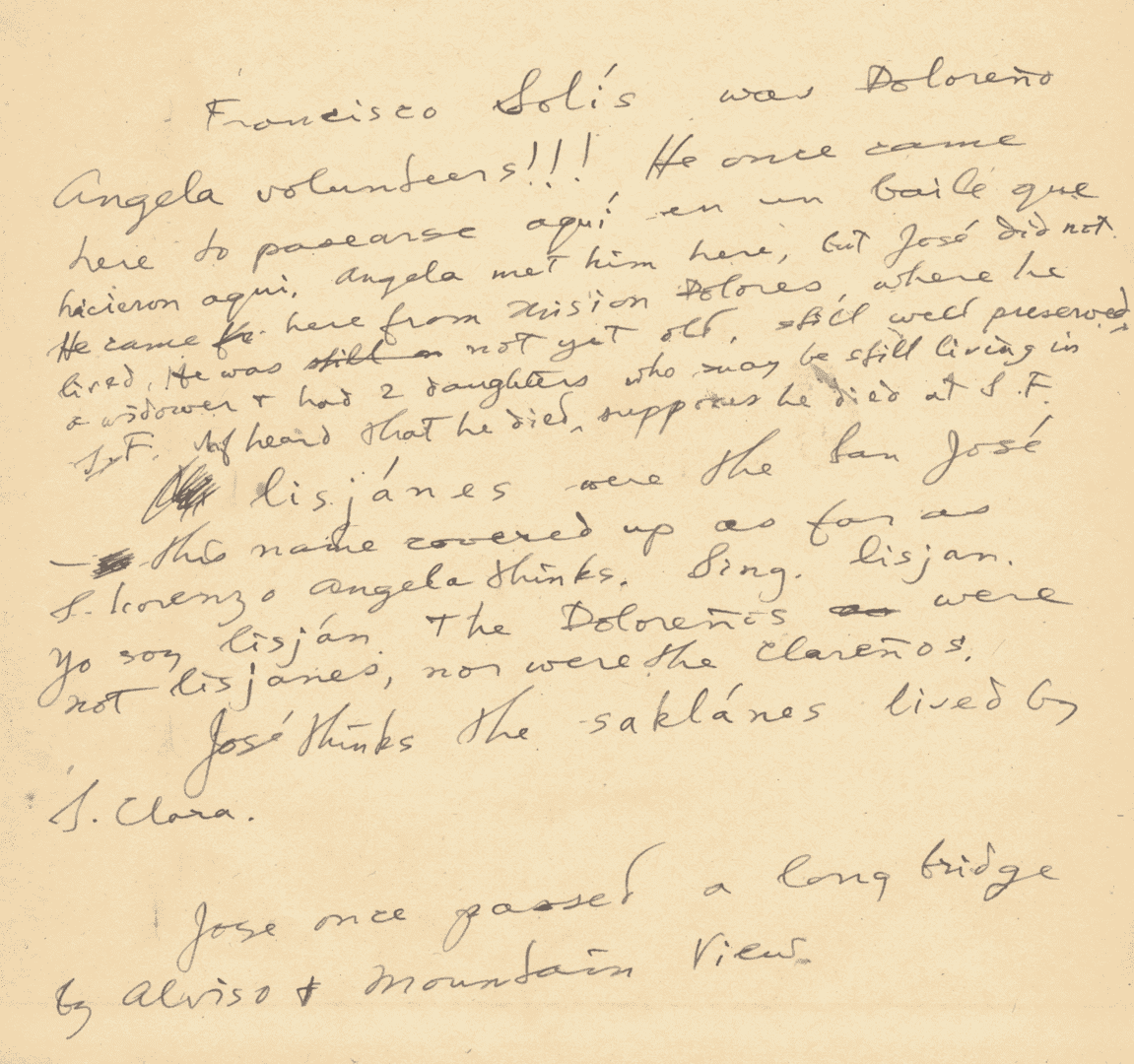

On page 95 of the PDF, a paragraph begins with “lisjanes were the San Jose.” It goes on to say that, neither the Doloreños, nor the Clareños, were Lisjanes.

lisjanes were the San Jose — the name covered up as far as S. Lorenzo Angelo thinks. 8ing. lisjan. yo soy lisjan. The Doloreños were not lisjanes, nor were the Clareños.

[Mention of Dumbarton Rail Bridge (opened 1910) at bottom of page?]

This entry includes a little more information about location. It states that the name Lisjan covered up as far as San Lorenzo. This is interesting, because the very first entry said Lisjan is the “Indian Name” of the Chocheños.

It’s also interesting, because the Chocheño-speaking Indians at San Lorenzo were called “Los Nepes”. Which means, they were considered a completely different group by Harrington’s interviewees.

Unfortunately, this entry only gives us a rough northern boundary to a possible Lisjan “territory”, certainly not enough information to pin to a certain geographic region. This also means that “Lisjan” was definitely not located in present-day Oakland, at all.

kana lisjanka, yo soy lisjan.

makin lisjanikma, we are lisjanes. approved lisjanikma but could not get tongue around it.

The next entries that we see, are on pages 105 and 106. While the phrases “yo so lisjan”, and “we are lisjanes” are present; so is a real problem.

There is no distinction between the words and phrases that are actually used/spoken in Chocheño–and given to Harrington; and, the words and phrases J.P. Harrington created, or invented, on his own, and “pitched” to his informant, and interviewees.

Using the information found in Harrington’s notes, I prepared the following visual aids.

I wanted to find the answers to a number of questions I had:

- Where is Lisjan? Is it in Oakland, Pleasanton, or somewhere else?

- Who are the Lisjanes? Are they a specific group, or family?

- Regarding what Angelo said about a Northern Boundary for Lisjan: is it possible the boundaries for Lisjan fall within the historic bounds of Mission San Jose?

Where is Lisjan? Is it in Oakland, Pleasanton, or somewhere else?

[If this is the only document you’re going by….] And, if the Northern bounds of the name “Lisjan”, were located just before San Lorenzo, that means that:

- Lisjan was not located in Oakland.

- Lisjan was not bound by the historical Mission San Jose property lines.

- Pleasanton was probably not called “Lisjan” by locals.

Who are the Lisjanes? Are they a specific group, or family?

Not much light is shed on who the Lisjanes are. While Jose Guzman probably declared himself Lisjan; it’s unclear the extent of Angelo’s affiliation to the name. At one point, one man touches his chest and tells Harrington that he is Lisjan in name, but his heart is from somewhere else.

Does this mean that Lisjan is somehow a transitory, or new affiliation based on where someone lives, now? Is this person simply saying something akin to, “I left my heart in San Francisco?” Or, “My heart yearns for home?” Or even something like, “This heart was made somewhere else; my blood pumps the blood of my ancestors, from a different place than here?”

We are told that the San Jose’s are Lisjan. The indian name for Chocheños from Mission San Jose are Lisjan. Indians from Santa Clara, and Dolores are definitely not Lisjan. Los Nepes aren’t Lisjan, either. And a tribe, from Sunol, the name of which no one could remember, was never affiliated with Lisjan.

This was one of the reasons I began to suspect that the bounds of Lisjan could be tied to the property lines of Mission San Jose.

But, alas, no matter which San Lorenzo you draw the Northern boundary of the name Lisjan upon, they always exceed the extent of mission property lines.